The rise and fall of Bugatti Automobili is a tale of immense ambition, unrelenting perseverance, boundless passion and, ultimately, ill fate. Its patriarch, the Italian automotive entrepreneur Romano Artioli, worked tirelessly for four decades in order to realise his dream of reviving the historic French marque and honouring the memory of its visionary founder Ettore Bugatti.

Using capital he’d earned through his empire of automotive dealerships, which encompassed brands such as Suzuki and Ferrari and spanned Italy as well as southern Germany, Artioli negotiated with the French government for two years to buy the Bugatti trademark and established Bugatti Automobili S.p.A. in October of 1987.

Work promptly began on a magnificent avant-garde factory in the Modenese province of Campogalliano, where Italy’s most talented automotive designers and engineers including Paolo Stanzani, Nicola Materazzi and Marcello Gandini had been lured to build the most technologically advanced supercar the world had ever seen, from scratch and entirely in-house.

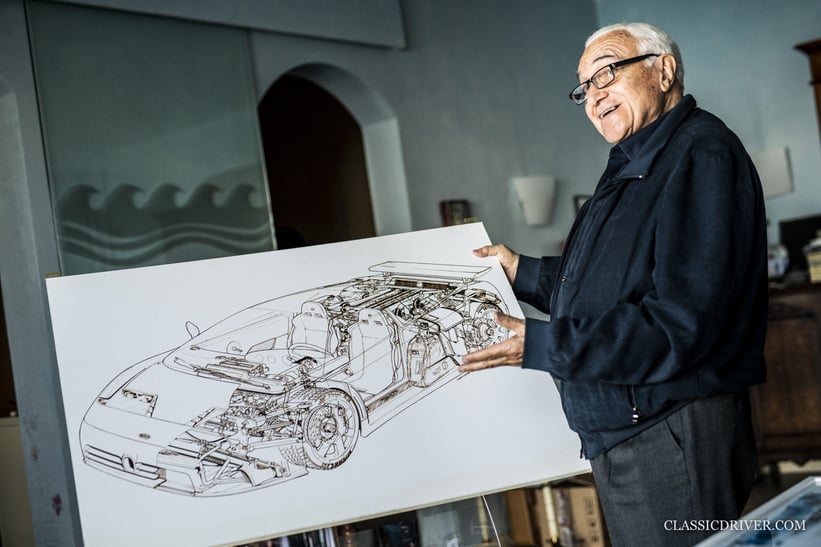

The result was the EB110, a 210mph, devilishly handsome, technological tour de force, with four-wheel drive, an aerospace-grade carbon-fibre chassis, and a 3.5-litre, five-valve-per-cylinder, quad-turbocharged V12 that developed 550HP. Suffice to say, the EB110 truly embodied Ettore Bugatti’s ‘Nothing is too beautiful, nothing too expensive’ mantra and, thankfully, inherited none of the fiery Latin temperament of its creators.

While the timing of its arrival was apt (the EB110 was launched in Paris to worldwide acclaim on 14 September 1991, Ettore Bugatti’s 110th birthday) and the car was lauded for its dizzying performance and unrivalled levels of refinement and practicality, factors beyond Artioli’s control including a global economic downturn and reportedly industrial sabotage thwarted the company’s success. On 23 September 1995, having only built some 115 production EB110s, Bugatti Automobili was declared bankrupt and closed immediately.

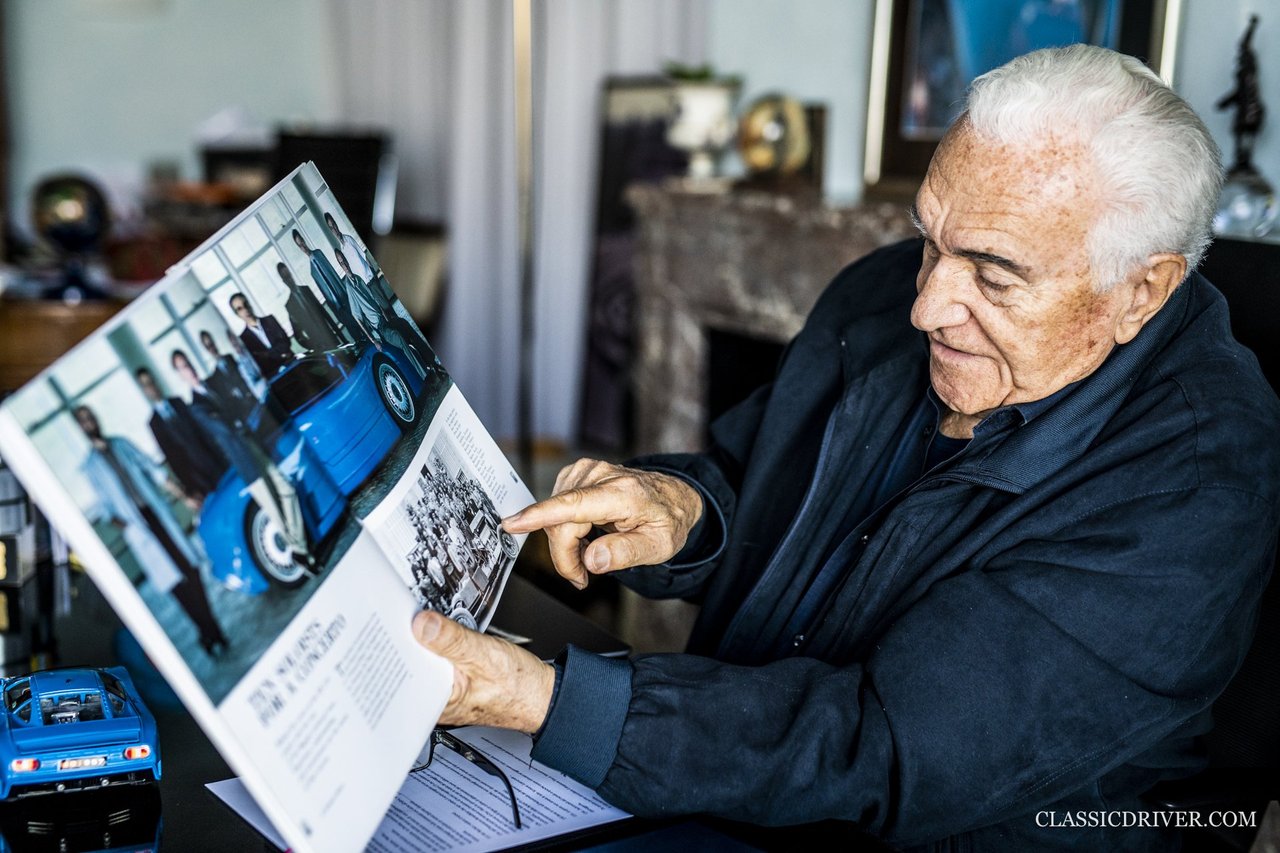

Today, 86-year-old Artioli splits his time between his office in Lyon and his family home in Trieste, Italy, which he shares with his wife Renata Kettmeir – who was instrumental in the fruition of Bugatti Automobili and headed up Ettore Bugatti, the marque’s luxury goods offshoot – and his beautiful daughter Isabella. He is sharp as a tack, fit as a fiddle, on occasion side-splittingly funny, and entirely tuned in to what’s happening in the world, particularly with regards to the automotive sector.

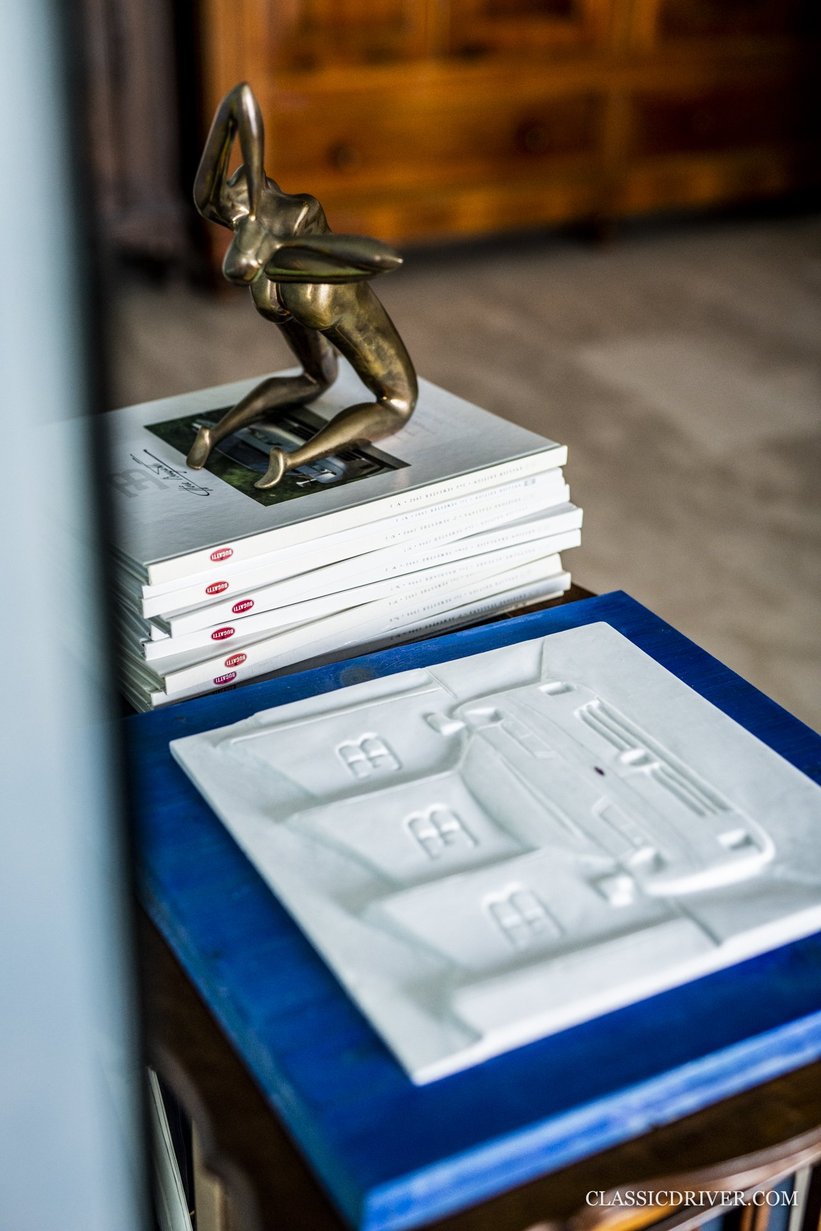

To this day, his opinions and feelings about Bugatti and its downfall are, understandably, of anger and sadness, strong and unwavering, though also of pride. However, with the world waking up to the rarity and then-unprecedented engineering excellence of Italy’s greatest forgotten supercar (including today’s Volkswagen-owned Bugatti) his baby is finally starting to get the recognition it deserves. We paid a visit to his stunning house on the Adriatic coast for homemade tortellini, Renata’s legendary tiramisu, and tales of the EB110 straight from the mouth of its charismatic godfather. Buckle up...

From where did your love for cars kindle?

I was born in Mantua, which was the land of the great Tazio Nuvolari. To watch him and his contemporaries drive and risk their lives every time they climbed behind the wheel was incredible. When I was 12, I read the book on how to obtain your driver’s license repeatedly and soon decided that cars and engines were my life. In Bolzano, where my family had moved, there was an important professional institute where I studied technology and machinery for eight hours every day. When I graduated, I looked to open a workshop because at that time it was difficult to repair cars that had been destroyed during the War.

Why did you decide to make it your life’s ambition to resurrect Bugatti?

In 1952, the news arrived that Bugatti had stopped producing cars. I was shocked because I’d always followed Bugatti’s activities and admired its work. From the First to the Second World War, Bugattis were renowned, not for their quantity but for their unrivalled quality. Bugatti was a family of artists. I’ve known a lot of engineers in my lifetime and, unfortunately, they tend to have expertise in one small area, which they cannot look beyond. If you have a broader background, in philosophy or the arts, for example, you can achieve much more. I decided that if nobody took care of the situation, I’d work and work and one day bring Bugatti back. I was 20 years old then and it took me 39 years to finally be able to achieve my goal.

How did you earn the money to fund Bugatti’s revival?

I imported cars. The first I was permitted to sell by the Vatican were Borgwards from Germany before I was nominated as the first General Motors dealer in Italy. In the same period, I started importing Suzukis. There were no Japanese cars in Italy at that time, so I wrote to Suzuki’s executives and told them I was ready to sell their cars. They answered that they weren’t interested but 15 days later, cars began to arrive. For 20 years, I was the number one importer of Japanese cars in Italy – I even sold the Maruti because it had air-conditioning, which no one else offered at the time in Europe. It sold like crazy!

Was getting the French, more specifically the people of Molsheim, on side important for you?

When I was negotiating with the French government to buy the brand, a lot of Italian companies were investing in France and the newspapers were saying that the Italians were taking over. Because of the circumstances, the minister said we couldn’t proceed but we managed to keep the discussions quiet and get the deal done. I looked at building the car in Molsheim, but it was impossible because Ettore’s son had relocated to Bordeaux after the War and all the old factories were gone, as were the technical people.

In France, Molsheim is like Maranello in Italy and Hethel in England. It’s a temple for Bugatti and the people are understandably very protective of it. I told them I couldn’t revive Bugatti on my own and asked for their help. It was so important for me to maintain the relationship between Molsheim and Campogalliano – I’m proud to say there are even marriages between people from either place!

Why was building such a radical factory so important for you?

I’d visited many factories in Europe to understand more about the automotive industry and I was shocked to find that most were terribly noisy, artificially lit, and didn’t have any windows. It felt like the workers were in prison. If I was going to enter the car industry, I wanted to build a factory that was totally different, which was open, air-conditioned and gave the sensation that you were outside in natural light. My younger cousin Giampaolo Benedini was the architect and did a superb job. Many other manufacturers came to visit my factory to see how things could be done. The people of Campogalliano are still shocked that they had the opportunity to work in such conditions taken away from them. Every year they have a meeting to remember and they continue to cry – it’s incredible.

Paolo Stanzani famously left Bugatti under a dark cloud – was it simply a case of differing opinions?

Stanzani was a gentleman who, in my honest opinion, was a talker and not an engineer. He did not understand anything – he only took ideas from others. I made a big mistake hiring him. It was stupid that he decided on a more flexible honeycomb chassis rather than carbon-fibre, for example. He said it was better for the performance – can you believe that?

Why did Benedini, the architect of the Campogalliano factory, end up finalising the EB110’s design?

Gandini designed a car that was absolutely terrible – it looked like a Lamborghini and was impossible to utilise. He was a good designer, but he did not realise that life moves on. His era was the wedge era when strong angles ruled. But he couldn’t look past that. I told him this car was not a Bugatti and that I wanted something softer that would appeal to more enthusiasts. So, when we changed the chassis, I asked Benedini to take a look because we didn’t have time to change everything – the launch date was fixed, after all.

Benedini told me it wasn’t his job, but I insisted he tried. Sure enough, he succeeded in bringing the car into the present and now, 30 years later, it still looks totally new. To encompass the large, horseshoe-shaped Bugatti grille was impossible so we finally agreed on the little one, which became known as the mousetrap. Gandini told me he didn’t recognise the new car and couldn’t accept it as his own. I told him thank you very much and he left.

Did you ever think you’d bitten off more than you could chew with such a wildly ambitious car?

We couldn’t play it safe. In order to honour Ettore Bugatti, we simply had to push the boundaries. The number of cars wasn’t so important to me, but rather the no-compromise quality and innovation. The Type 57SC Atlantic was like a helicopter for the road – this was the capacity of Bugatti, to continue to invent and do things differently to the others. Throughout the entire project, I always followed Ettore’s ‘Nothing is too beautiful, nothing too expensive’ philosophy.

What are your memories from the launch day in Paris, on Ettore Bugatti’s 110th birthday?

Of relief, because it very nearly didn’t happen! A week before, Renata had to go to Paris because the authorities there had thought that we wanted to stage a small event but had found out that we’d actually invited more than 5,000 press and industry execs from around the world. They thought it was too dangerous, so we had to hire hundreds of private security guards to form a perimeter around the entire event at the Place de la Défense. They also told us we couldn’t do overt advertising, but Renata got around that by arranging a huge bouquet of flowers in the shape of the Bugatti logo. All the girls were screaming after Alain Delon as he drove with Renata off down the Champs-Elysées. No one had any idea that we’d finished the car when it was in the truck on the way to Paris.

Arguably your most famous customer was Michael Schumacher – how did that come about?

During that period of time, there were many specialised manufacturers building sporty cars – McLaren, Jaguar, Porsche, and so on. A German magazine organised a group test and invited Schumacher along to drive. Once he drove the EB110, he said it was a car unlike any other and simply beyond compare. He immediately came to Campogalliano and bought a yellow Super Sport with a blue GT interior. He didn’t ask for any form of discount – he was an absolute enthusiast and I know he enjoyed that car a lot!

At what point did you realise things were not going as forecast?

We worked hard to present the car around the world and people were generally enthusiastic, despite the global financial crisis. The Americans were in shock after the Gulf War because they spent so much money and the yen had soared. This was a shock for us because Suzuki was our lifeblood – it gave us the opportunity to revive Bugatti. Suzukis became 50 percent more expensive and at the same time, Fiat was having a crisis because nobody was taking care of the quality over there. It couldn’t sell cars, so it insisted on re-evaluating the lire to boost exports. To add insult to injury, the economy weakened in Italy and the market shrunk.

At this point, I decided to push the activities of Bugatti, but I discovered afterwards that three of our directors were paid off by our rivals. Our suppliers were blackmailed to stop distributing to us, and because we only placed comparatively small orders, they had no choice but to oblige. Orders suddenly dropped, too – the first to let us know were the Japanese, who called to tell me the director I’d sent there to present the car was not a good person. These people were very professional and knew exactly what they were doing.

If we did something, the others were informed. The press coverage of the Paris launch was extensive… in every country other than Italy. The main newspaper in Italy spoke of the new Lancia Delta and ‘another Italian brand’. It was forbidden to talk about us. Journalists were even sent information claiming we were financed by the mafia! When I started, I couldn’t imagine that I’d suffer such an attack.

Could you describe the day the factory was closed?

It was absolutely awful. Everything was lost, from personal belongings to official archive photos and documentation. One week later, the president of the administrative board arrived to see the factory and she soon realised that Bugatti Automobili was not just another company that hadn’t been paying its bills. I paid all our employees until the very end.

Do you have any regrets looking back?

To have not had the opportunity to launch the EB112 super saloon to the world. That was a really incredible car and actually more enjoyable to drive than the EB110 GT. The engine, a naturally aspirated, 6.0-litre V12, was mounted behind the front axle, the chassis was built from carbon-fibre, and the suspension was so light as it was inboard. As a result, the car handled like a go-kart. Giugiaro says the EB112 is the most important car he ever designed, and he was so excited when he realised it was a true modern-day interpretation of the legendary Art Deco Bugattis.

How do you feel when you see an EB110 today?

It fills me with great emotion. It took 40 years before I was finally granted permission to build the EB110 and then there were seven years of total war. The people involved in the project were wonderful, and it was these people who made the car so special – they understood the quality we were keen to uphold. To lose it in such circumstances was such a shock. Today, the EB110 is still on another level – its contemporaries were simply not as accomplished.

Photos: Rémi Dargegen for Classic Driver © 2019