There hardly is any better key to twentieth-century history than the automobile. If future archaeologists study the dusty artifacts of our era, it will probably be the last surviving sports and racing cars, which will tell them the most about the technical possibilities and social aspirations of the Homo automobilis on the eve of the third millennium. In retrospect, it seems almost visionary that Filippo Tommaso Marinetti already put the aesthetic relevance of a race car ahead of the formal meaning of ‘Nike of Samothrace’ in his Manifesto of Futurism in 1909. In fact, the early years of the automobile, in the first half of the twentieth century, are kind of the antiquity of our age of speed, which is slowly but surely coming to an end.

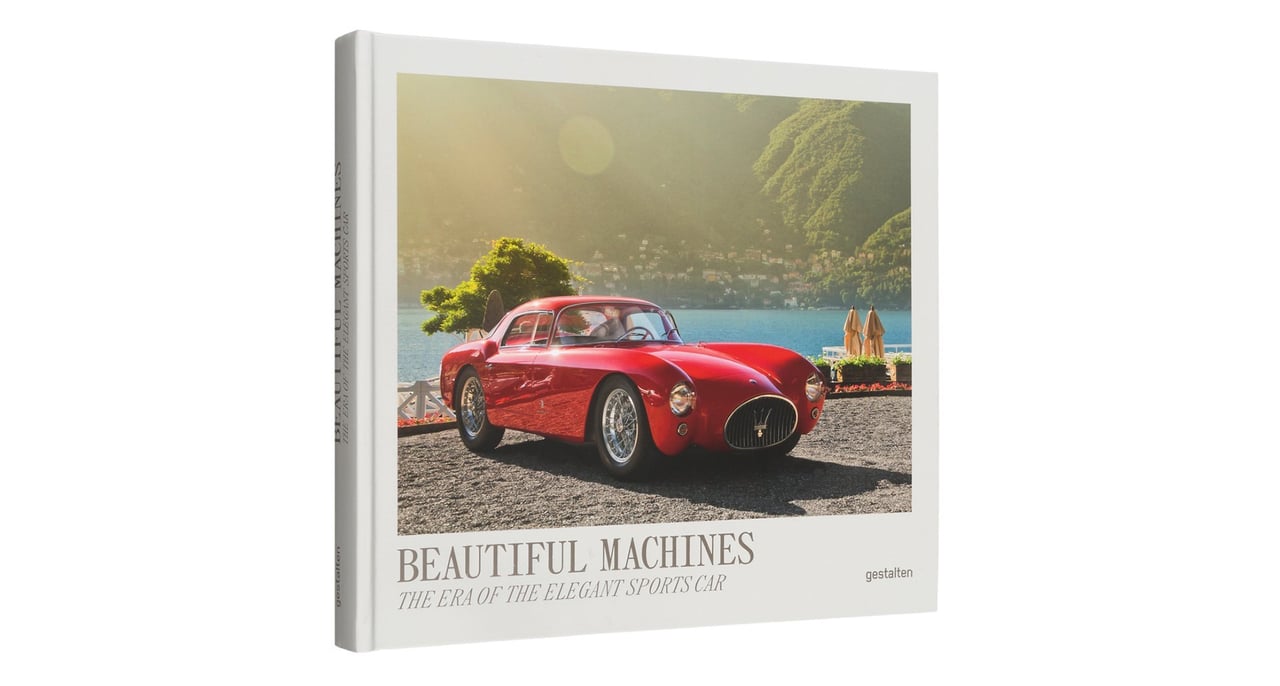

Since the earliest days, the purest and, at the same time, the most powerful embodiment of the automotive principle was the sports car – a mythical being, born in the spheres of racetracks and given to the people on the road, now domiciled somewhere between fantasy and reality. Sports cars were avant-garde, carved in sheet steel and aluminium, and they were mobile sculptures of progress at the forefront of technological development. Major brands such as Porsche, Ferrari, Maserati, or Mercedes-Benz primarily owe their present-day appeal to their classic sports cars, which brought engineering innovations and motorsport experience into a desirable form tamed for civilian life on the streets.

Ingenious designers such as Ettore Bugatti created not only mechanical but also aesthetic masterpieces. Its social relevance and global appeal as an object of desire and projection of dreams and expectations, however, reached their pinnacle after the Second World War. It was no wonder that many of the most fascinating sports cars of all time emerged during the economic boom of the post-war years: the horrors of war had vanished, and in the radiance of the sun, the world shone like a landscape of unlimited possibilities at the right and left side of the road, which could be explored fast and on your own at the wheel of one’s Gran Turismo. Whereas the generations before had allowed their trunks to be hauled onto carriage-like sedans, suddenly a weekender bag was enough, stowed on spartan emergency seats or in a small luggage compartment. Anyway, you did not need much more than a couple of fresh shirts, sunglasses, and your passport on the road trip to freedom.

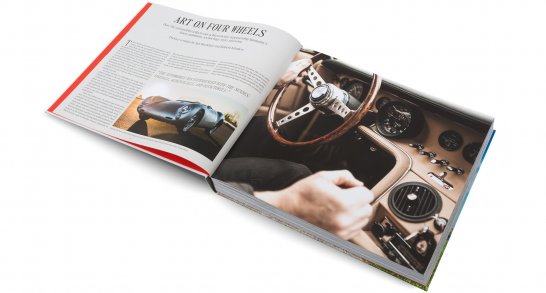

For those who roared through the serpentines of the Alps with a Mercedes-Benz 300SL ‘Gullwing’ or spurred a Lamborghini Miura on a Mediterranean coast road at that time, possibilities must have indeed felt unlimited. While photographers such as Edward Quinn and Slim Aarons were able to capture the glory and splendour of the young European haute-volée with the camera, designers like Battista Pininfarina and Giorgetto Giugiaro succeeded in casting the dreams and longings of their time into amazingly beautiful body shapes.

Meanwhile, the USA was already a step ahead: the new longing of the Americans was space – and with the ‘Space Age Design’ the rocket’s futurism also found its way into the secular formal language. The fact that the street cruisers did not defy gravity but rolled heavy and bubbling over the Main Streets of small-town America and burned gallons of gasoline did not matter: they still got their wings.

With the first oil crisis in the 1970s, for the first time, it became clear to the world that the triumphant advance of the automobile would not continue to gain momentum forever. Still, sports cars were powerful symbols of progress – but instead of conquering the stars, the new models were now above all the competition with better and faster acceleration and top speed values to stick out and boost sales of the in-house volume models. The aesthetics of sports cars also changed in the 1980s and 1990s: The mantra of this time was faster, louder, flatter, wider. And although the potential of most super sports cars of that time could no longer be exercised on public roads, their buyers were still given the theoretical opportunity, and a mighty wing sticking up into the sky that vicariously symbolised the enormous horsepower.

At the beginning of the new century, the automotive industry is suddenly confronted with the most elemental paradigm shift since the invention of the internal combustion engine. In the face of global structural changes in digitalisation, and the current challenges of climate change, it suddenly becomes a matter of thinking about future mobility from scratch. While the big brands defended their established business models, ambitious start-up companies like Tesla and Rimac put the first sports cars with electric drive on the road – demonstrating that automobiles do not need to have booming eight cylinders under the bonnet to fascinate. At the same time, the attitude of the young generation towards the automobile changed: instead of ownership and status, suddenly comfort and flexibility became important. If you live in a big city, you may prefer to have the right car from the ‘car-sharing fleet’ instead of owning your own four wheels at your front door. Research centres have already been examining the abolition of the driver and the complete autonomy of mobility. The automobile, once a symbol of progress and individual freedom, is experiencing its greatest identity crisis. The sports car has summarily been declared an enemy of the state.

It was complicated – and still is. Although the signs of mobility have changed rapidly, the dream of the extraordinary automobile continues. Classic collector cars have multiplied their values in recent years and are traded for millions. The market for expensive customisation and sports cars in limited edition series is flourishing. Independent creative brands such as Singer, Emory, or Automobili Amos, with their restomods, occupy those niches for highly emotional and down-to-the-minutiae ‘dream cars’ that were neglected by the major automobile brands on their growth path. The world of automobiles is changing rapidly, becoming more intriguing, more colourful, and more creative than ever before.

Meanwhile, in the old automobile industry, the realisation has prevailed that there is no better aggregator of social change and the acceptance of new technologies, as positive enthusiasm and optimistic symbols of a joyous future. The few built BMW i8 or Porsche 918 Spyder may have done more for the fascination of electric mobility than all the Toyota Priuses put together. Sustainability itself has become a status symbol – and why should it produce less elegant, beautiful, or desirable forms of automobiles than the designers did in the days of golden coachbuilding or the winged Space Age Futurism eras? Released from their duties as suitable everyday transport vehicles, in the future, the sports cars and Gran Turismos must offer even more unfiltered driving experience and even more emotionality than ever before. In a networked and completely automated world, they still have their place – as breathtaking vehicles of self-development, personal freedom, and individuality.

'Beautiful Machines' - out now

An extended version of this text by Jan Baedeker and Robert Klanten has been published as a preface to the new Gestalten book Beautiful Machines written by Blake Z. Rong and illustrated with beautiful photos from Classic Driver house photographers Rémi Dargegen and Mathieu Bonnevie. The coffee table book is available now in Europe and will be on sale worldwide from 4 December 2019. You can order your copy online in the Gestalten shop.

Photos by Rémi Dargegen / Mathieu Bonnevie / Drew Phillips / Girardo & Co via Gestalten