In times of automotive megalomania and aesthetic arbitrariness, it can be helpful to revisit the creative minds that pushed for a highly inventive but also functional, democratic, and humble approach to design during the glory days of modernism in the 20th Century. Designers such as Ferdinand Alexander ‘Butzi’ Porsche, who was trained at the anthroposophical Waldorfschule and did a stint at the influential Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm before developing the ascetic yet everlasting Porsche 911. Or the creative poster couple Charles and Ray Eames, who revolutionised industrial design and architecture in mid-century California with their rapid prototyping philosophy and use of humble materials including plywood, glass-fibre, and plastic. But while ‘Butzi’ and the Eames’ can only be studied through their work, one of their contemporaries and fellow advocated of good form is still very much alive.

As an architect and designer, Carl Gustav Magnusson worked at Charles and Ray Eames’ Los Angeles studio in the late-1960s and shaped the image of Knoll as the furniture brand’s long-time director of design. Today, he still enjoys the restless lifestyle of a curator, lecturer, mentor, inventor, and design visionary, commuting between his homes in New York and Milan and, when he gets the chance, indulging in his lifelong love for classic cars.

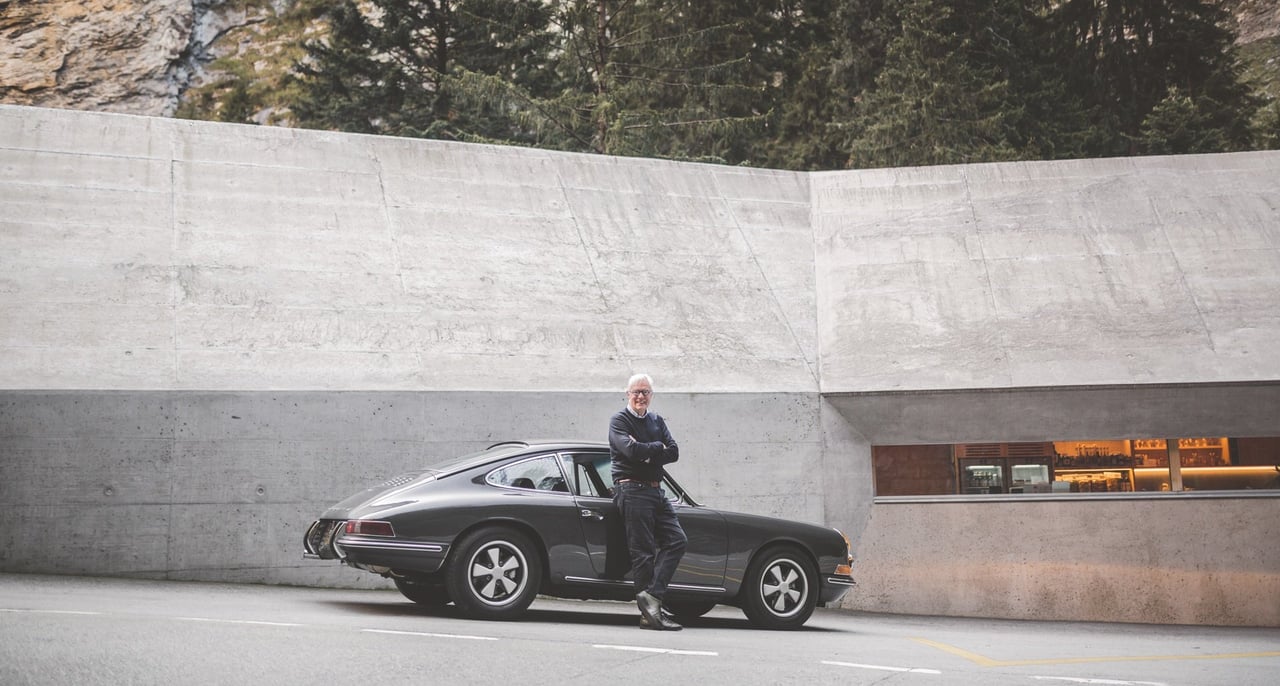

We meet Carl Gustav on a bright September day in the centre of Andeer, a small alpine village in the Swiss canton of Graubunden. Having driven here from Milan in the early sunlight across the San Bernardino pass, the energetic designer has brought his latest project car: a rather unusual Porsche 912. With its stylish yellow à la Française headlights, period California number plates, and glossy slate-grey paint reflecting the cloudless, deep-blue sky, the car looks nothing short of stunning. But like everything Magnusson touches, this Porsche is more complex and eclectic than first meets the eye. We jump into the passenger seat and set off, upwards towards the famous Splügenpass. With vast walls of granite and pine trees flying by, it’s time to dig a little deeper into the roots of the project and, of course, Carl Gustav’s design philosophy.

Could you tell us a little bit more about the car and how it came to be in your possession?

It’s a Porsche 912 from 1968. When I found it in California, it had some surface rust and had been badly repainted. It was then restored in Pennsylvania by Bruce Baker, a real master of his art. He’s worked on Porsche 356s and early 911 SWBs all his life and took this 912 as one of his last projects before he retired.

What was the idea behind the rebuild?

I did not want to turn the 912 into another 911 – that would have been pretentious. I rather wanted to emulate the humble spirit of the 912, keeping it simple and underlining the original design approach. There’s nothing luxurious about this car and I like to think that ‘Butzi’ would have approved of it.

The cockpit appears very minimalistic, yet a lot seems to have been modified. Could you please talk us through it?

I’ve intentionally kept it in the spirit of the Porsche 912. As an inexpensive sports car, I wanted things to look industrial, functional, and purposeful. Instead of leather luggage straps and woollen carpets, there’s a lot of standard rubber. The only colours are grey, black, and a little bit of metal and chrome. I used British aircraft seatbelts with simple aluminium clasps. The steering wheel is standard, I just polished the edges, and the Heuer logo on the dashboard doesn’t make the clock more accurate, but it just looks better. I replaced the plastic piece on top of the dashboard with a tailor-milled Masonite piece painted in the car’s body colour – just like on the early Speedsters. I also removed the cigarette lighter and ashtray to make the cockpit even simpler. My belief is that the passenger should have a horn, as they might see things that the drivers doesn’t, so I put one in. For the power supply to the battery, I used a simple Bosch stock switch, which I like the industrial look of. And instead of the cliché Porsche logo, I have an Ampelmännchen, an East German mascot, on my keychain.

What did you change on the exterior of the car?

I had it painted Slate Grey as the colour works wonderfully with the shape. I changed the headlights and switched them to yellow, though I kept the fog lights white and also kept the original indicators – if you look closely, you can actually see some cracks. I replaced the standard mirrors with small aftermarket motorcycle mirrors. I kept the original 5.5inch wheels and had them refinished with details painted in Slate Grey and titanium nuts. The Vredestein tyres have the correct dimensions but are produced in new chemical compounds. It’s not been lowered and that’s another reason the car rides so nicely – it’s in balance with its original intention.

You even gave the Porsche logo a twist…

Well, there’s a guy in Maryland who can give a metal object any look you desire. So I sent the badge to him and told him I wanted it to look like tin: polished on the edges, but darker in between. The circle on the bonnet is just a discreet graphic reference to the classic racing roundels, in anticipation of some action.

The closed engine cover is one of the car’s most distinctive features – what’s the story behind it?

As a four-cylinder car, the 912 needed less air cooling than the six-cylinder 911. Some people even called it an oil-cooled car. But still, Porsche kept the 911’s cooling grille. I thought a closed engine cover would benefit the car’s flow of line, so I designed a new cover with very few cooling vents. It was crafted from aluminium by a talented craftsman in California.

So, what’s the car like to drive?

It drives very well. It has Weber carburettors and the s0-called ‘big bore’ kit, boasting 1,750cc instead of the standard 1,600cc. The engine’s been improved, not so much as to make it faster but to improve reliability. This summer, I’ve driven the car from London to north Wales, then down to Milan, back up to Munich for Luftgekühlt, and now to the Engadin without any problems at all.

As an architect and industrial designer, from where does your fascination with cars stem?

My father was an engineer. When I first told him that I wanted to design automobiles, he told me designing automobiles is like designing ties. Many years later, I realised that Ralph Lauren owned one of the greatest car collections in the world – because he had designed ties. When I finished studying architecture, I wrote a letter to Charles and Ray Eames in Venice, California, and asked if I could work for them. A few weeks later, I received a reply saying yes and that I should come on over. So, I moved from Sweden to California. That was in 1968. I’d just finished designing the local luxury automotive importer’s showroom and had gotten a discount on a new Morgan. It was driven by Peter Morgan himself to a harbour in the UK and then shipped to the US on an open boat. When I arrived on the Westside of New York City to pick it up, it was completely filthy. When the customs official saw this anachronism of a car from the 1930s, he waved me through without having to pay any tax duty. So, we drove off – me, my wife, and two kids – in this filthy Morgan, across the United States and all the way to California.

How was it working for Charles and Ray Eames?

At the Eames’ office at that time, there were 14 or 15 people working. We worked on projects including the National Aquarium in Washington DC, which never actually came about, the refurbishment of the IBM Mathematica exhibition. It was a wonderful time of my life. After starting my own business, I got a call from the furniture company Knoll in 1974. I quickly found myself living in New York, working on its products, graphics, and showrooms. Knoll sent me all around the world – I lived in Paris, London, and Milan. But after 29 years, I thought I should figure else what else I could do. In conclusion, it hasn’t been much different. For the past 14 years, I’ve had my own industrial design practice and given lectures at universities.

What is the key piece of insight into design that you have gained in the last 50 years?

The lecture my students like best is called ‘3,500 years of design in 2,000 seconds flat’. It’s a history of cultural influences on design. A successful design process is always a unique combination of existing ideas. Your smartphone is nothing new, it’s just old ideas put together. That was the brilliance of Steve Jobs – he saw connections everywhere. Once a combination of ideas is successful as a design object, it seems so obvious. But imagine three people like us sitting on a table 30 years ago, each having a telephone next to his plate, with cables and all. That would have been absurd! Many successful innovations in technology began with an idea that initially appeared flawed, like putting the engine in the back of the car instead of the front. I like how Porsche has stuck it its formula and continuously advanced it over 70 years. It brings it very close to perfection.

The classic Porsche 911 is still considered to be the ‘thinking man’s sports car’ and the 912 is even more subtle. Why is there no real appreciation for cheap and simple, yet clever, sports cars anymore?

Around 60 years ago, the luxury industry found out that people love to pay more. Why is a Rolex as expensive as it is? Simple: because it sells better at a higher price. There’s a joke about millionaires in Russia. One guy asks, “what did you pay for the Rolls-Royce?’, and the other responds, “I paid one million dollars”. “You’re crazy,” comes the reply from the first man, “I could have gotten you the exact same for two million dollars!”

What fascinates me about the Porsche 912 is its fundamental simplicity and humbleness. It’s not about performance or showing off. It’s all about functionality and relies on as few parts as necessary. And its reliability is due to the engineering genius of its makers. For me, reliability goes hand in hand with honesty – both in cars and real-life relationships. And that car is honest!

Photos: Robert W. Cooper for Classic Driver © 2018