Plenty did, though. It’s hard to pick just a few stories from the 160-odd pages of anecdotes that pack Touch Wood – not to mention the hilarious recollections of his contemporaries. Choosing almost at random, there was the time he was stopped for speeding in the Cromwell Road in London while on his way to take part in a television programme on road safety… or the erroneous newspaper reports that he had been killed in a road accident, resulting in his wife receiving letters of condolence – to which Hamilton replied with the words ‘looking forward to seeing you soon’.

‘Drunken Duncan’ (as he was popularly but perhaps unfairly known) never let a serious racing career get in the way of his off-track exploits, but this gentleman racer’s skill at the wheel was indisputable. Indeed, the great Argentinean racing driver Froilan Gonzales claimed that, in the wet, Hamilton was the fastest driver in the world.

Lucky escapes

One of the greatest Jaguar works drivers of the 1950s, it’s said that Hamilton’s racing career came about because he found post-War life rather dull – hardly surprising when you consider his close shaves with death throughout the war years. Hamilton joined the Fleet Air Arm, the branch of the Royal Navy responsible for naval aircraft, and on several occasions was lucky to escape with his life.

His career in motorsport started with sprints and hillclimbs in a supercharged MG R-type – a car he once transported to the Brighton Speed Trials in a lorry. Coming down the hill into Guildford, Hamilton ‘saw the splendid honeycomb radiator of a Bugatti in the outside rear-view mirror’, so he moved over and waved the priceless Bugatti past. But the car hung back. A bit further down the hill, the Bugatti accelerated and drew level with Hamilton, at which point he saw there was no one in it: “The awful truth dawned on me – it was my own car, gathering speed fast.” He’d forgotten he was also towing his Bugatti 35B behind the lorry, and the story ends with a concrete lamppost snapped in two.

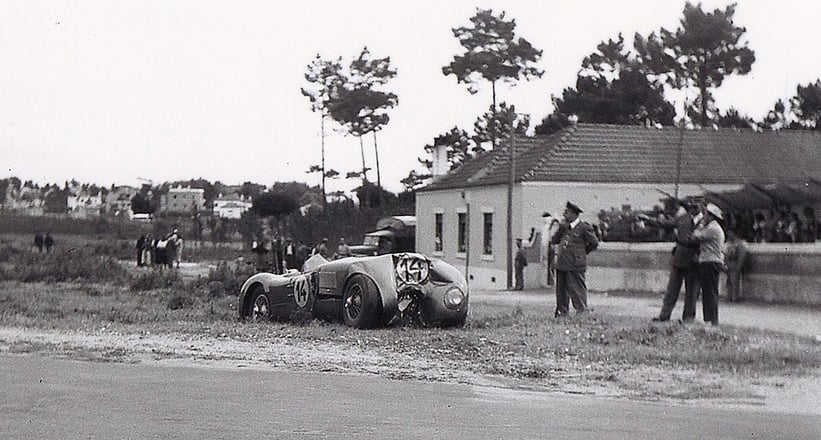

As well as the MG and that T35 Bugatti, Hamilton also competed in – among others – the famous ERA ‘Remus’, a Grand Prix Maserati and a Talbot-Lago. But in a career that encompassed five World Championship Grands Prix and 18 non-Championship Formula One races, it was of course Le Mans in 1953 that saw his greatest victory, teamed with co-driver Tony Rolt.

Overcoming the odds... and a hangover?

Rolt’s natural dignity is the perfect foil to Hamilton’s delightful tales and, if Hamilton had an interesting wartime history, it was nothing to Tony Rolt’s – one of the men who planned to escape from Colditz by building a glider in the attic of the castle. Rolt himself disliked personal publicity and, as his Daily Telegraph obituary stated, he avoided Colditz reunions, saying, “Escaping was not a game. Nor was it fun. It was a duty.”

But at Le Mans in 1953, the pair shared a common disappointment. During pre-race practice their Jaguar C-type was disqualified on a technicality, so they headed to a bar to drown their sorrows. After a night of solid drinking, at 10am they saw a Mark VII Jaguar pull up and out got Jaguar supremo William Lyons, with the news that they were ‘back in the race’ – which would be starting shortly. According to Hamilton, they overcame their hangovers by drinking brandy during the pit-stops (although Rolt strongly denied this).

Whatever the truth of it, the pair came through an eventful race (at one point a bird struck Hamilton in the face – at 130mph – and broke his nose) to take the chequered flag and win the world’s greatest endurance race. Few lives can capture the true spirit of motor racing in the early 1950s better than Hamilton’s combination of driving skill, roguish charm and derring-do.

Photos: Getty Images / Duncan Hamilton Ltd.