One of our most vivid motorsport memories is of a Porsche 911 Carrera RSR Turbo 2.1 at Le Mans Classic in 2014. It was the dead of night and as the Martini-liveried monster bellowed past us through Indianapolis and towards Arnage, its enormous and awkwardly protruding turbo was aglow with heat. At that point, we remember thinking there wasn’t a cooler car on the planet. And in the presence of that very Porsche today, with its gargantuan whale tail and hilariously wide hips, the fact remains the same.

Little did we know of the car’s extraordinary story back in 2014, or that of the 911 Carrera RSR 2.8 we’re also joined by and with which the turbocharged car shares its chassis number. You often hear stories in the classic car world about multiple cars claiming the same identity and how their respective owners fight tooth and nail to declare theirs the real McCoy.

In the case of these two Porsche factory prototypes, however, there is no smoke and mirrors. Simply put, the Carrera RSR 2.8 is R5 (Porsche’s internal codename for the car) in its original 1973 specification. The Turbo 2.1, on the other hand, is a fastidiously built recreation of R5 when it was in its 1974 blown configuration, utilising countless original parts – including virtually the entire body – and stamped with the same chassis number but with a ‘/2’ suffix.

You might be wondering why the owner went to such great lengths to have a second RSR built honouring R5 in its later spec. The answer is simple: as the very first 911 equipped with a turbocharger, it represented the start of a devastatingly successful bloodline of production-based racers and arguably counts as one of the most significant Porsches of them all. Still confused? Bear with us.

The 911 Carrera RSR prototypes built by Porsche for the 1973 World Sports Car Championship were all given codenames beginning with ‘R’ and served two purposes: to win races and act as rolling testbeds for new technological evolutions. For that reason, they often raced in the prototype class rather than the Group 4 category for which they were homologated, benefitting from a more relaxed set of rules and a resultant upgrades package that was as relentless as it was effective.

It also meant the ‘humble’ 911s were pitched directly against thoroughbred prototypes designed from scratch by the likes of Ferrari and Matra. Suffice to say, they more than held their own. In fact, Carrera RSRs won both the Daytona 24 Hours and the last-ever Targa Florio and placed a remarkable fourth at Le Mans.

The more classical of the two Porsche 911s pictured here at the Lurcy-Levis private test-track near Magny-Cours in France – chassis 911 360 0576 or R5 – was built in Weissach as one of those full-fat Works Carrera RSR prototypes. Included in the M491 package that rendered it so were big wheels and fat tyres, flared arches, thinner-gauge aluminium bodywork, and a twin-plug 2.8-litre flat-six that kicked out an ample 300 horses.

When R5 made its competitive debut at the Six Hours of Vallelunga on 23 March 1973, it marked the first time a 911 raced with full Martini sponsorship. While Gijs van Lennep and Herbert Müller finished an impressive eighth overall, at the 1,000km of Dijon a few weeks later, the same expert driver pairing dominated the GT class and earned R5 its first silverware. The car’s next race, the Spa 1,000km, was equally successful, George Follmer and Reinhold Jöst snatching the car its second consecutive class victory.

An accident at the Nürburgring in May resulted in R5 missing Le Mans and it was returned to Weissach. And it’s at this point that the car’s life veers off on an entirely different trajectory. Anticipating a rumoured new silhouette category for the 1975 season, Porsche saw an opportunity to use the technical knowledge it had gleaned from both the RSR and the utterly dominant turbocharged 917/10 and 917/30 Can-Am prototypes to develop a potent new blown 911. It was the 911 that was in the showrooms, after all – it made perfect commercial sense, particularly given the prominence of endurance racing at that time.

Norbert Singer was assigned to oversee the project and promptly called on the services of R5. As what was essentially the mule for the Carrera RSR Turbo 2.1, R5 became the very first Porsche 911 to be fitted with a turbocharged engine. The lightweight motor had the same bore and stroke as the original (and already decade-old) 911’s flat six in order to meet the CSI’s 2,143cc cap for turbocharged cars but was largely the same as that found in the naturally aspirated RSRs.

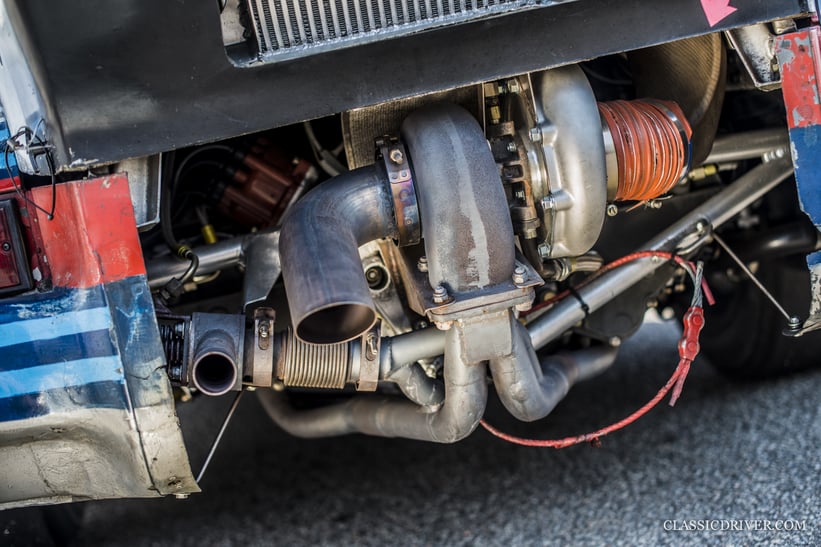

A socking-great KKK turbocharger was slung out below the rear wing and force-fed compressed air to the engine via a large top-mounted intercooler. Lag was a major problem, as was chronic overheating, but the motor was effective, developing an explosive 500HP.

Porsche’s engineers went to town developing a radical new glass-fibre body to package the new powerplant. R5 received ground-hugging air dams up front and a near-horizontal Plexiglas rear window that fed into the giant whale tail in order to reduce lift and increase high-speed stability. Employing many 917-derived components, particularly in the complex suspension system, led to a significant weight saving, though the subsequent three Carrera RSR Turbos were based on the much lighter 3.0 bodyshells.

Porsche never intended to race R5 but owing to a timing clash with Le Mans, it was called into active service one last time in June of 1974 for a 1,000km race at Imola. The only race the car entered in its later configuration (complete with new window-mounted air intakes) ended prematurely thanks to a turbo failure. After numerous strong results, including second overall in the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1974, Porsche retired the Carrera RSR Turbo. Its DNA was used to develop the next generation of turbocharged 911 racers, the 934 and 935, and ultimately the formidable 936, 956, and 962 prototypes. R5 was sold and headed Stateside, where it would remain until 2012.

Fast-forward to 2001 when the somewhat questionable decision was taken to restore the car back to its original Carrera RSR 2.8 specification. Of course, it was in that form that R5 took its race wins. But after its turbocharged transformation, much of the original car was lost. Furthermore, its significance as the world’s first turbocharged Porsche 911 and the spiritual predecessor to some of the most successful racing cars in motorsport history was arguably more interesting from a collector’s point of view than its two class victories.

Regardless, the decision was final, and the well-known American Porsche specialist Gunnar Racing did an exquisite job in returning R5 to its 1973 specification. Crucially, Gunnar realised the importance of preserving and storing every redundant piece removed from the 1974 car, acknowledging that a future owner may choose to revert R5 once again. These parts were subsequently sold to Manfred Freisinger in Germany and although restoration was mooted, no further action was taken on its part.

In 2012, a Porsche collector in France bought the restored R5 and Sébastien Crubilé of Crubilé Sport was entrusted with its care and maintenance. After much discussion between the two, they decided to resurrect R5’s second life and build a second car utilising the dismantled 1974-spec parts.

A vast body of research was compiled, Crubilé leaning on his contacts at the Porsche Museum, the extensive photography Gunnar had captured during every phase of R5’s restoration throughout the 2000s, and of course his own expertise. A 911 2.4 bodyshell was sourced, sympathetically restored so as to match the original bodywork’s incredible patina and stamped with the chassis number 911 360 0576/2. This made it clear from the outset that the car is a homage to R5’s lost second life and in no way claiming the identity of the ‘real’ car.

Whether it’s the beguiling patina of the ’74 car or the sheer extremity and size of its swollen bodywork, it’s certainly the car towards which we’re drawn the most (that’s not to say the 2.8-litre car lacks presence in any way). The largely original paint of the RSR Turbo is blistered and cracked and there are dirt and grime caked in its countless crevices, amassed during both its period and historic racing careers.

Painstaking effort was made to recreate its exact test-mule state – no mean feat when the three other blown RSRs differ greatly in their details. Suffice to say, it’s every bit as authentic mechanically. Crubilé left no stone unturned and, as a result, perhaps knows the car better than anyone. That’s why when the ex-Le Mans racer swings open the featherlight door and invites us to hop in, we practically bite his hand off.

Experiencing a Porsche 911 Carrera RSR Turbo 2.1 at the limit from the passenger seat ranks right up there with the memory of watching the very same car flying past that night at Le Mans in 2014. You know it’s going to be fast but you’re not quite sure how all that power is going to be served. Sébastien hustles the car beautifully and it’s a real pleasure to observe just how he wrings every last drop of performance from the heavily turbocharged car. The sensation is other-worldly. As you’d expect, the boost arrives late in the rev range, but when it comes, it feels like you’ve been slung to the moon by a giant slingshot.

The noise, the smell, and the frenetically wavering turbo dials mounted to the dash are overwhelming, but there’s no time to fret. Just as we expect Sébastien to brake for an upcoming corner, he does the exact opposite and keeps his foot buried, maintaining the boost pressure throughout the entire curve and thrusting us out the other side. The grip is extraordinary, testament no doubt to the 917 wheels and suspension setup, and you’d never expect a car of this era to cling to the road with such determination. The distinctive chirrup of the wastegate that rings around the cabin with every downshift only adds to the magic.

Debates could rage for weeks as to which of these incredibly special Porsches lays a stronger claim to the R5 title, such is the complex and nuanced nature of their story. But the simple fact that both cars, in their respective naturally aspirated and turbocharged forms, happily co-exist in the same ownership means they simply don’t need to. To put it simply, the world is a better place with two R5s than it is just one.

Photos: Rémi Dargegen for Classic Driver © 2019