Silicon Valley and its founding generation gladly claim that the offices of California were where young pioneers orchestrated the upheaval of the digital industry. But even in England during the bleak post-War years, automotive garages were rife with the spirit of innovation. The start-up of Colin Chapman, from which Lotus was born, and the father-son Cooper team, the first to mount an engine amidship, both originated in small backyard workshops. Their contemporary Eric Broadley can also be included in this gifted group of motorsport constructors, all of who created competitive racing cars with limited means.

The spirit of innovation

Incidentally, they all belonged to the ‘750 Motor Club’ — named after the cubic capacity of a pre-War Austin Seven — and, each weekend, competed against each other with their modified contraptions. The 1956 ‘Broadley Special’, however, with its tuned Ford side-valve engine, already bore the DNA of the legendary Lolas to come. Enzo Ferrari was probably blissfully unaware of the ingenious young Englishman at the time — that was until the Lola Mk6 GT burst onto the scene. Its genes were to be used as a basis for the Ford GT40, which was set to give Maranello a big fright.

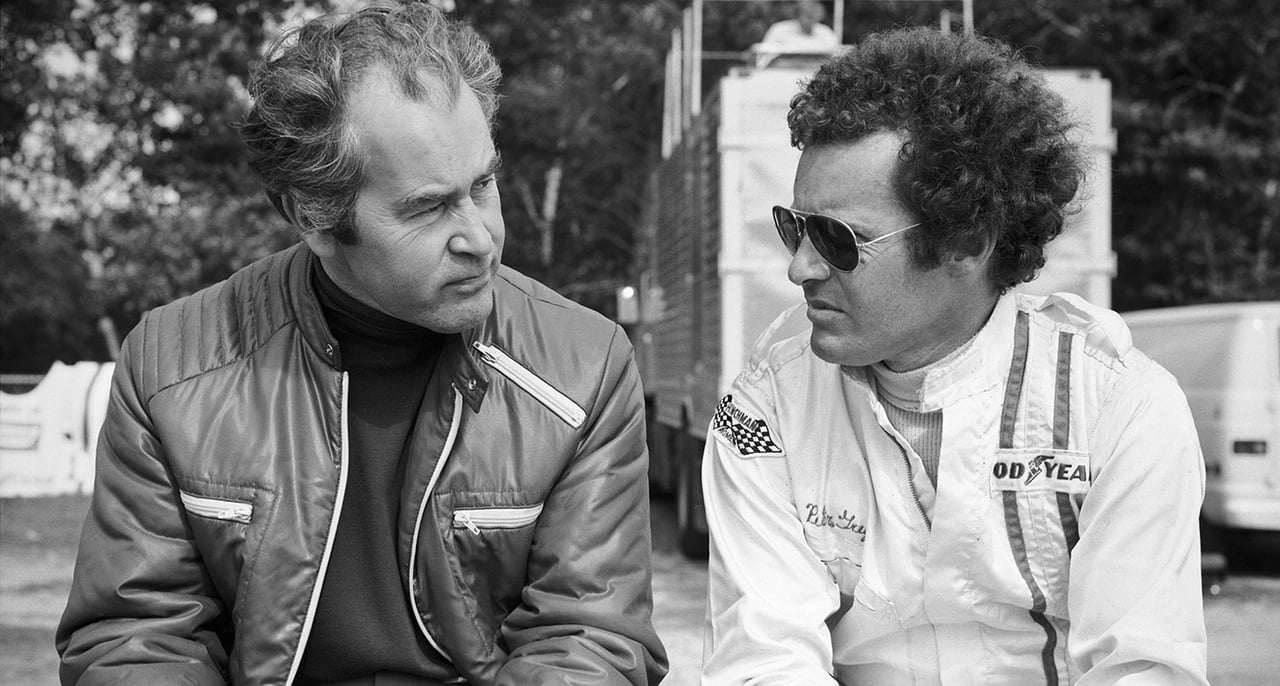

Eric Broadley was born in 1928, to a family of gentlemen outfitters in the London borough of Bromley, and the fact he was always pictured smartly dressed, even while casually chatting with the likes of John Surtees or Mario Andretti in the pit lane, is probably more thanks to his upbringing rather than the fashion of the time. Incidentally, or maybe purposefully, the family’s successful emporium was located next to Lola’s first headquarters. And while the attraction of motorsport was strong, Broadley was initially trained as a quantity surveyor. Inspired by his cousin Graham, he quickly became fascinated with motorsport and began to develop and race his own cars. He also soon realised that his cars were quicker without him at the wheel, so he settled on designing them for the rest of his life instead.”

What Lola wants, Lola gets

It’s not really known whether the song ‘Whatever Lola Wants’ from the musical Damn Yankees inspired Broadley’s cars’ name. But from the opening of Lola Cars International in West Byfleet in 1959 to its sad end in the 1990s, following a ruinous renewed attempt at Formula 1, this auspicious female name adorned the aerodynamically sophisticated, feather-light, organically curved bodywork of such legends as the Mk6 and the T70 — cars that still raise pulses at historic motorsport meetings today.

From the beginning, Broadley saw his core competency in racing and never aspired to design cars for the road. And if he did follow the old mantra of ‘race it on Sunday, sell it on Monday’, then it was with the view of selling racing cars to privateer customers. And so it was when his agile Coventry Climax-powered Mk1 vanquished the rivals from Lotus and Cooper and set the lap record at Brands Hatch in 1958. Customers queued up to buy replicas of the car, which provided Broadley with a much-needed financial lifeline. Later, in 1963, Broadley further signalled his motorsport ambitions when he presented the Mk6 GT at Le Mans. With its almost flat roofline, doors that cut into the roof for easier ingress and egress, innovative glass-fibre components, and brutal 4.2-litre Ford V8, it was a promising sign of what was to come from the visionary designer.

Cue the skills-scramble

Broadley narrowly made it to Le Mans with the new car and, alas, it retired in the 15th hour, thanks to transmission damage. This was new ground for the largely undeveloped car, after all. What happened next, however, was to be woven into the fabric of the Lola legend. Henry Ford II had wanted to return to the global motorsport stage for several years, and after a bold-but-failed attempt to buy the Scuderia Ferrari, he and the brass from Detroit discovered Broadley and his innovative prototype. Broadley was neither a mechanic nor an engineer, but there were few who understood the optimal relationship between the engine, gearbox, chassis, and slippery bodywork.

When Eric Broadley came on board as a consultant, the GT40 project was already in its development phase. The Mk6 formed the basis, especially since the Ford V8 had already been fitted into it. In addition, a separate development team in Slough, England, was employed, as there were no real financial constraints. Despite being plagued with political, performance, and reliability issues, in 1966 the GT40 — now with seven litres of displacement — dominated at Le Mans, claiming 1-2-3 in the standings, ahead of the Ferraris. And the car wasn’t done at the great endurance race — it won the following three races, too.

Deafening silence

But by then, Broadley was long annoyed by the skills-scramble from his Ford adventure. During his 18 months of involvement in the project, however, he did gain experience and sufficient means to dominate in the following decades with such models as the T70 in the Can-Am series and at Le Mans and the T90 at Indianapolis. Up until the 1980s, Lola was still one of the leading racing car manufacturers. Along the way, Lola chassis have been powered by engines from Ford, Chevrolet, Aston Martin, Honda, and BMW and were piloted by such legends as Graham Hill, John Surtees, Roy Salvadori, Al Unser, Jo Siffert, and Jacky Ickx.

Formula 1 was Eric Broadley’s dream and, ultimately, his failure. He’d made his debut in the top-flight in 1962, with the Mk4 driven by John Surtees and Roy Salvadori. By the end of the 1980s, Lola was supplying just two unsuccessful Formula 1 teams, and in 1997, having found a potent sponsor in MasterCard, the racing team managed just one outing at Melbourne before it was forced to file for bankruptcy. The talented man, who’d instilled so much fear in Enzo Ferrari, died just a few months ago. But his innovative and successful cars stand testament to the British garagistas who dared to push the boundaries and challenge motorsport’s old guard. Suffice to say, Lola almost always got what she wanted…

Photos: Alvis Upitis, Tony Triolo, GP Library via Getty Images / Rémi Dargegen for Classic Driver © 2017