Sadly, it wasn’t to be: despite being launched at the 1984 Birmingham Motor Show to a rapturous reception from public and media alike, Lotus was in a familiar phase of turmoil.

Its eminent custodian had passed away a couple of years prior, but not before instructing the company’s Chief Engineer Tony Rudd to build a new V8 engine (codenamed Type 909); it was to have as much in common with the slant-four still operational across the Lotus family as possible, while conjuring 320bhp and 300lb ft.

Meanwhile, other Lotus engineers were working on a new active suspension system for the firm’s Grand Prix machines that would eventually filter down into the road cars. When the Etna was revealed in Birmingham, it was promised that it would be the first road-going Lotus to receive this sophisticated suspension, along with traction control, ABS and noise cancelling – and, of course, Rudd’s 4.0-litre Type 909 engine which ultimately produced 335bhp and 295lb ft.

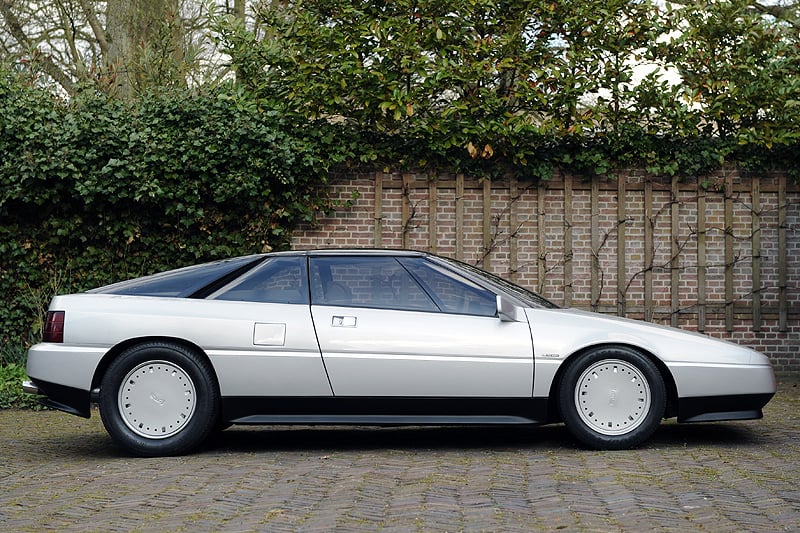

However, although it resembled a fully-operational car, the Etna concept was actually a styling model fashioned from wood, clay and glassfibre. While Lotus took care of the engineering in-house, it had commissioned Italdesign of Turin to style the Etna and shipped the elongated Esprit chassis to Italy. What came back was a handsome, aerodynamic design – but it was created to stir interest in the production version, rather than being a fully-functional representation of it.

Lotus’s financial troubles subsequently put the Etna on the back-burner, and GM’s buyout in 1986 extinguished any lingering developmental embers. Ever-soaring fuel prices led the new owners to believe Lotus’s bottom line would be better served by a cheap sports car rather than an all-out supercar; hence the front-wheel drive Elan of 1989. By this time, the unique Etna had long been consigned to storage at Hethel.

It resurfaced in 2001 when it crossed the block at a Coys auction, and soon afterwards made its way into Olav Glasius’s significant Lotus collection. Glasius wanted to resurrect the Etna from its now-decrepit state, and enlisted the services of ex-Lotus engineer and restoration specialist Ken Myers. Upon evaluating the work needed to bring the Etna back to its 1984 glory, Myers stumbled across something unexpected: beneath layers of clay and glassfibre nestled a gearbox and, more importantly, a Type 909 engine.

Only two Type 909s were built; the other had been retained by Lotus. When Lotus had sent the Esprit chassis to Italdesign, it had also sent the engine and gearbox to help Giorgetto Giugiaro with the packaging of his creation. Following this unexpected discovery, Glasius tasked Myers with the arduous job of transforming the styling model into a running car – a job which included forming the rest of the car’s mechanicals, including suspension borrowed from an Esprit. A new Perspex canopy also had to be made, after wind had relieved the Etna of its original unit while it was being trailered down the M1. After just a year, Myers' handywork meant the Etna could parade round Goodwood under its own power, rather than remaining inert as it had done at the N.E.C. almost 20 years prior.

Depending on your interpretation, the first British ‘supercar’ was probably the Jaguar XJ220 or McLaren F1. But had the Etna not fallen victim to Lotus’s seemingly endless financial troubles, it might at least have earned a mention in that type of company; perhaps as a foretaste if not a predecessor. Sadly, it might not be the last Lotus to be culled as a result of fiscal anxieties – but here’s hoping any subsequent casualties are afforded the same dedication and respect that the Etna found in its later life.

The Etna is soon to be sold as part of the Glasius Lotus collection featured in Bonham's Goodwood Festival sale.

Photos: Bonhams & Italdesign