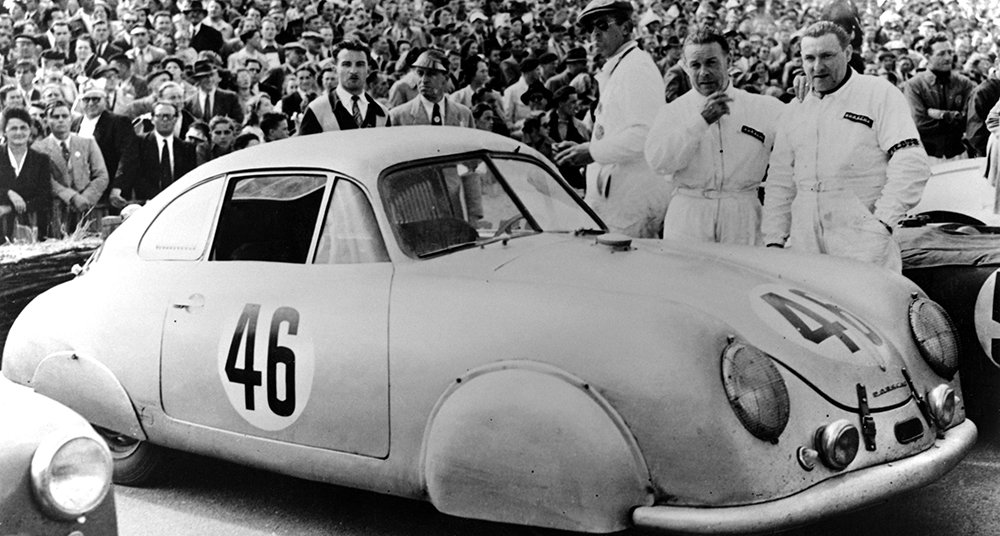

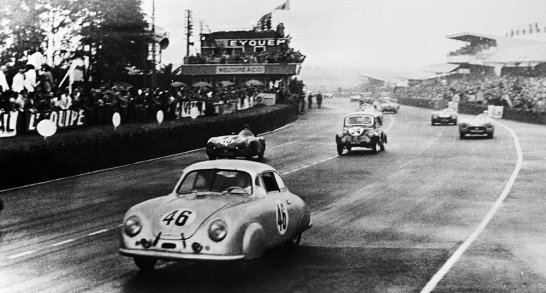

What do you do with your Le Mans-winning racing car once it’s been retired from active service? Why you sell it, of course! Porsche certainly wasn’t sentimental about keeping hold of the 356 Gmünd SL Coupé in which French drivers Auguste Veuillet and Edmond Mouche claimed victory in the 1100cc class (and an impressive 20th overall) in the legendary endurance race in 1951 – the marque’s very first foray onto the international motorsport stage.

Fitted with a detuned engine, chassis #063 was exported to America by the East Coast concessionaire Max Hoffman, and promptly sold to the California-based racing driver John von Neumann who, during the course of his ownership, removed the roof in a bid to keep the car competitive. In 1957, it was sold to Chuck Forge, who would cherish and race the 356 right up until his death in 2009.

Few of the many people who witnessed the little red roadster over the years could possibly have known of its Le Mans provenance, not least Cameron Healy, the ‘died-in-the-wool’ Porsche enthusiast and one of the first people to commission an ‘Outlaw’ 356 from Rod Emory. He’d dreamt of owning the car since first seeing it at the Monterey Motorsports Reunion, and when Forge sadly passed away, that dream became a reality.

Healy employed the expertise of Rod Emory – the founder of Emory Motorsports, who coined the term ‘Outlaw’ to describe its restomod 356s – in the inspection process prior to buying the car, and a number of anomalies led the duo to believe this could, in fact, be the Le Mans-winning Gmünd SL Coupé. Over two years of painstaking ‘automotive archaeology’ ensued, after which their hunch was proven right. It was then that the decision was taken to restore the car to the exact specification and state it was in when it took the Circuit de la Sarthe in 1951.

Developing his first roadster prototype into a coupé was a logical step for Ferry Porsche in the late-1940s. Around 50 road-going alloy-bodied 356 Coupés were built in Gmünd, Austria, after the firm was forced to relocate there during the War. In 1951, once production had been established back in Stuttgart, Porsche made use of several leftover aluminium bodies from Gmünd to build its very first racing cars – a move that, if successful, could potentially prove lucrative.

As the necessary modifications were made, including the addition of an enlarged fuel tank and aerodynamic wheel spats, so the SL Coupé (denoting ‘Sport Leicht’) was born. Le Mans in 1951 was its very first outing – solo, as its sister car crashed in testing – and the 45bhp car averaged over 70mph for the entire 24 hours. It was long-distance reliability with which Porsche would later become so synonymous.

The most obvious obstacle for Rod Emory and his team to overcome in the restoration process of #063 was the fact the car was no longer a coupé, and thus only 80% complete. As such, a new roof section, dashboard and inner structure had to be fabricated from scratch. This was achieved first with the use of 3D scanning technology in order to build a faithful wooden buck (just as the original cars were built) before the new aluminium panels were hand-beaten into shape. Emory prides himself in using traditional craftsmanship techniques, and the finish is so much better for it. And where original parts could not be sourced, they were manufactured in house.

For Emory, to work on a genuine early Gmünd 356 with many aesthetic features that inspire his own ‘Outlaw’ 356s, such as the grated headlight covers and leather bonnet straps, was a real treat. From every single angle, the car is simply astonishing, but it’s not until you peer closer that you understand the lengths to which he went to capture every last detail. In fact, we don’t think we’ve ever seen such a faithful restoration – no stone was left unturned.

For example, the tool chest mounted behind the seats contains a spare wiper blade that can be attached to a mount atop the windscreen should the main wipers fail, the passenger seat reclines to allow the passenger to rest (this car was driven to and from Le Mans, remember), and the small vent in the middle of the front bumper can be manually opened from the cabin to cool both the car and its occupants. And using hundreds of period photographs as reference, Emory was able to ascertain certain quirks unique to this car, such as the small dent in the rear wheel spat where the mechanics had been swiftly changing the wheels, or the piece of hose lodged behind the front right headlamp to better light the apexes.

Think of Porsche and Le Mans and our minds conjure Gulf-blue-hued images of 917Ks flying down the Mulsanne Straight, or Jacky Ickx caressing a Rothmans-liveried 956 through the Dunlop curves. But this humble 356 was, in fact, the car that sparked Porsche’s transfixion with the great French race. The company acknowledged its authenticity in 2015 and subsequently invited Healy to exhibit the car in its semi-restored state at the Rennsport Reunion at Laguna Seca. A Pebble beach appearance followed, and Healy hopes one day to return the car to its spiritual home of Le Mans. For now, however, the glitz and glamour of Hollywood will have to suffice – a fitting location for such a legendary car.

Photos: Drew Phillips